# Contemplation 2

# Points

For many painters including Kandinsky, the point represents the atomic unit of visual expression. In Point and Line to Plane Kandinsky outlines the origins of the point: a geometric classification and in the written word as a period. By placing a period in different and especially illogical places in a sentence he attempts to reveal an inner voice for the point.

This contemplation doesn't have any interaction, but demonstrates Kandinsky's argument in a timed-based way.[1] As we can see, the placement of the point however illogical sometimes changes the meaning and always changes the cadence of the sentence. From here, Kandinsky argues that by pushing the point farther away from understood constructs like the written sentence, the point's own inner voice can be witnessed. For this reason, Kandinsky believed the point can be viewed up close or composed of other points. Kandinsky compares points to both stars in the galaxy and nitrates forming in a petri dish.[2] Painting in particular adds an unexpected element of variation once the brush, pen, or other tool hits the canvas.

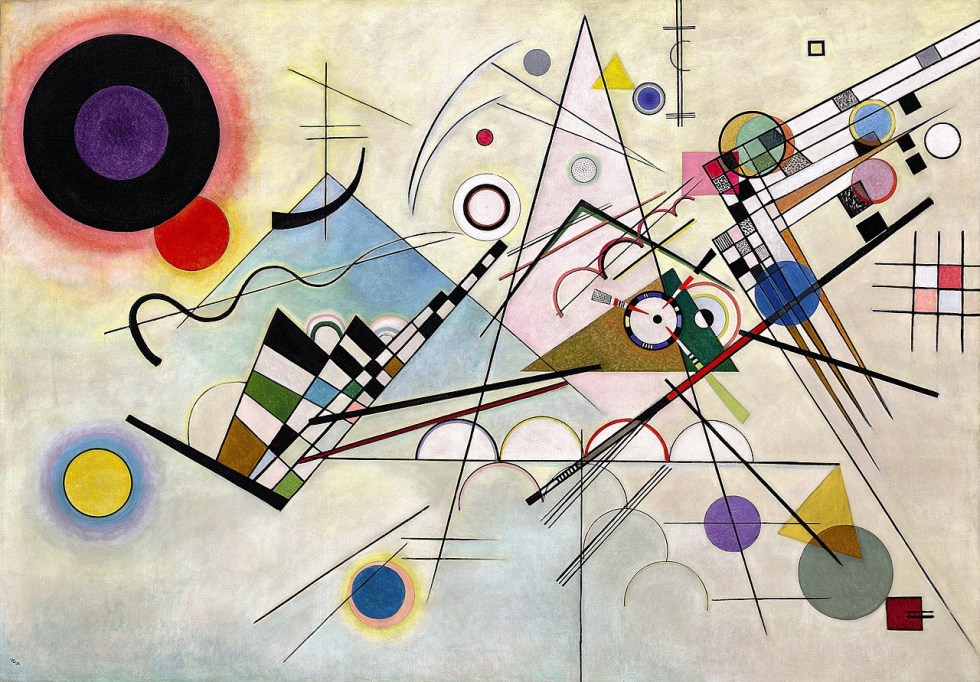

This composition is a recursive animation of one point made of many other points.[3] The iterative nature to this animation opens up the interpretation of what a point can be. This complicates paintings like Composition 8. Is each circle a point? Only the circles without visible outlines? Does a point have to be small? Does it have to be round?

Source code for this contemplation can be found here: link. ↩︎

Kandinsky, Point and Line to Plane. Kindle Edition. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1926. ↩︎

Source code for this contemplation can be found here: link. ↩︎

Kandinsky, Wassily. Composition 8. Oil on canvas. 140 x 200 cm. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1936. Screenshot courtesy of Guggenheim ↩︎